China’s Megadam on the Yarlung Tsangpo: A Looming Challenge for India’s Water Security

China’s construction of a massive hydropower dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo River, near India’s northeastern border, has triggered global environmental concerns and heightened regional tensions. Expected to surpass the Three Gorges Dam in scale, the project has intensified the Tsangpo Dam dispute, with India fearing potential disruption to downstream water flow. The absence of a water-sharing agreement fuels the Tsangpo Dam dispute, while experts warn of seismic risks tied to the dam’s location. As strategic and ecological stakes rise, the Tsangpo Dam dispute is emerging as a key flashpoint in India-China relations.

The Yarlung Tsangpo River and the Tsangpo Dam Dispute: A Looming Challenge?

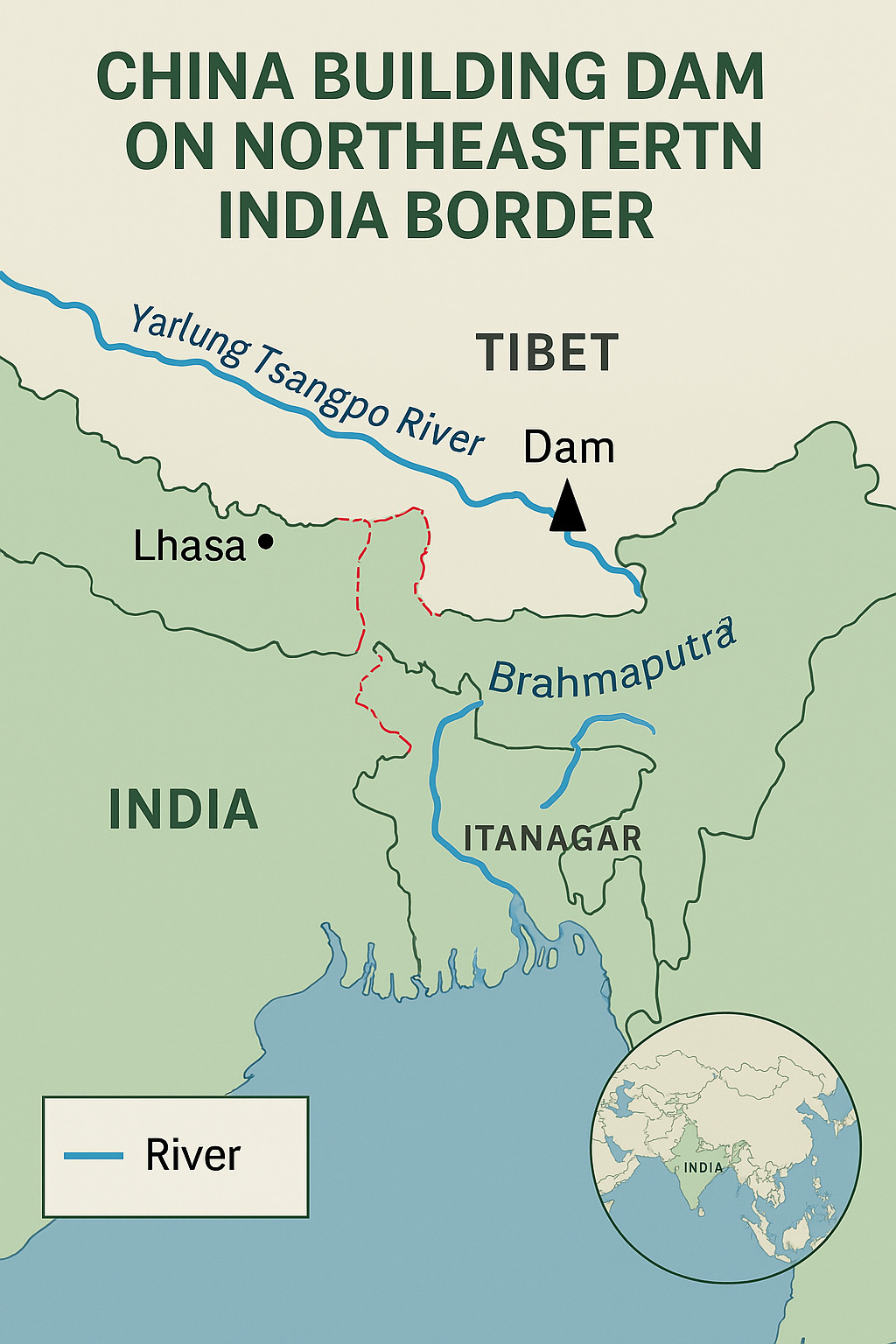

The Yarlung Tsangpo River, also known as the upper stream of the Brahmaputra River, originates in western Tibet and flows eastward across the Tibetan plateau. After a dramatic U-turn at the “Great Bend,” the river descends into Arunachal Pradesh in India where it becomes the Siang River, later joining tributaries to form the Brahmaputra in Assam.

This river system is not only ecologically significant but also vital to the livelihoods of millions of people in northeastern India and downstream in Bangladesh.

The Dam Project: Scale, Ambition, and Location

China’s plan involves building a hydropower dam at Medog County, located near the Great Bend of the river. Here are the key specifications of the project:

-

Location: Medog, Tibet Autonomous Region (approx. 30 km from Indian border)

-

Projected Cost: USD 137 billion

-

Expected Power Generation: 60 gigawatts (GW) — three times the capacity of the Three Gorges Dam

-

Annual Energy Output: Over 300 billion kWh

-

Planned Completion Year: 2030 (Phase 1 by 2028)

If completed as proposed, this dam will be the world’s largest hydroelectric project, dwarfing any other in capacity and scale.

Why This Project Raises Red Flags

🟠 Geopolitical Implications

The dam’s location—close to the India-China Line of Actual Control (LAC)—is causing unease in New Delhi. Relations between the two countries have remained strained since the 2020 Galwan Valley clash, and any infrastructural development near sensitive borders is closely scrutinized.

India is particularly concerned about the potential weaponization of water. While China claims the project is purely developmental, the unilateral control over water flow into India could serve as a strategic lever during diplomatic or military standoffs.

“Water can be used as a tool of diplomacy, but in a disputed zone, it can turn into a threat,” remarked a senior Indian defense analyst.

🟢 Environmental and Seismic Risks

-

The Eastern Himalayas are one of the most seismically active zones in the world. Experts have warned that a structure of this scale in an earthquake-prone region poses catastrophic risks.

-

The Great Bend is home to pristine biodiversity, with many endemic plant and animal species. Unchecked damming could disrupt natural habitats, riverine ecosystems, and migration routes of aquatic life.

-

Sediment flow and nutrient transfer downstream will be affected, altering agricultural productivity in the Brahmaputra basin, especially in Assam and northern Bangladesh.

🔵 Downstream Impact on India and Bangladesh

India and Bangladesh both depend heavily on the Brahmaputra for:

-

Drinking water

-

Agriculture

-

Fisheries

-

Hydropower (existing and planned)

Any change in river flow, whether through controlled water release or sediment trapping, could trigger flooding, drought, or erosion in the lower riparian states.

Key concerns include:

-

Loss of water during lean seasons

-

Sudden discharge during monsoons causing floods

-

Loss of delta fertility due to sediment blockage

India’s Response: A Dam for a Dam?

In response, India has announced its own countermeasures:

-

A 10 GW hydropower project on the Siang River in Arunachal Pradesh is under review.

-

The Indian government is also exploring options to accelerate dam construction in Upper Assam to ensure downstream water security.

-

India is strengthening its satellite-based hydrological monitoring systems to track river flow and dam construction progress in Tibet.

Additionally, India has raised the issue at bilateral forums and is calling for greater transparency in transboundary river projects.

What International Law Says

Under the UN Watercourses Convention, upstream countries are expected to notify and consult downstream neighbors before undertaking any major hydro projects. However, China is not a signatory, giving it legal leeway in these developments.

This has sparked demands from Indian policy experts and environmentalists for the creation of a regional water governance treaty involving all major stakeholders, including Bangladesh.

Conclusion: A Wake-Up Call for Water Diplomacy

China’s dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo is more than just a mega infrastructure project — it is a test of water diplomacy, regional cooperation, and climate foresight. While hydropower can serve green energy goals, the project must be balanced with environmental safeguards, local consultation, and geopolitical restraint.

As tensions simmer along the Himalayan frontier, it’s critical for India and its neighbors to adopt a proactive water security strategy — one that respects both the power of nature and the importance of cross-border trust.